Results

Rates of poor self-rated health were highest among those who had stopped drinking, followed by those who never drank. The rates of poor self-rated health among non-drinkers were significantly higher than the rates of poor self-rated health for any of the groups who reported alcohol consumption.

Conclusions

Among those who drank alcohol, there was no evidence that any pattern of current alcohol consumption was associated with poor self-rated health, even after adjustment for a wide range of variables.

Thursday 30 July 2015

Healthy drinkers

A bit more evidence for the deniers to deny. At this stage, I think it's fair to call them that.

Wednesday 29 July 2015

Outdoor smoking ban consultation

The public consultation on the 'voluntary ban' on smoking outdoors in Brighton and Hove is online. It's a simple survey which only takes two minutes to complete so please do so. There are various nosy questions about sexuality, race and so on, but you can ignore them.

Give 'em hell...

UPDATE

Simon Clark is getting déja vu...

Give 'em hell...

UPDATE

Simon Clark is getting déja vu...

We all know where this is heading.

It reminds me of the three or four year period before MPs voted for a national workplace smoking ban.

Prior to the 2005 election the Labour government showed very little desire to introduce a comprehensive, nationwide ban. Instead it was rumoured Tony Blair was happy to leave it to local authorities to decide their own policy.

One day therefore I would find myself addressing a council committee in Plymouth. A few weeks later I'd be doing the same in Middlesbrough, then St Albans, and so on.

A decade or so later we're facing a similar situation, but the issue now is outdoor smoking.

Tuesday 28 July 2015

Good riddance to bad sock-puppets

I'm pleased to able to bring glad tidings for a change. DrinkWise North West,

the taxpayer-funded lobby group, has had its state-funding withdrawn.

Since nobody in their right mind would give it money voluntarily, this

naturally means that it has been closed down with immediate effect. Its Twitter feed has already disappeared.

You may recall DrinkWise as the Department of Health front group that used public money to campaign for alcohol advertising bans and minimum unit pricing (MUP). For the latter, they set up a sock-puppet website - anonymously, at first - which made the ludicrous claim that MUP would reduce the price of some drinks. The rest of its campaign literature had a similarly uneasy relationship with the truth.

There is no doubt that DrinkWise were a lobby group (how nice it is to speak of them in the past tense). It's difficult to find any part of their website that was not devoted to encouraging people to 'join the movement', 'act now' or 'write to your MP'. Despite being 100 per cent state-funded, they were proudly and openly engaged in political campaigning.

Since most of their income came from local authorities, they would have been in breach of the Department for Communities and Local Government's new 'anti-sockpuppet clause' which states:

Presumably this was a large part of the reason for its funding being withdrawn. We must also presume that DrinkWise's counterpart across the Pennines, Balance North East, will soon also be consigned to the dustbin of history. Balance North East's room-mates at FRESH should be heading for the door shortly afterwards, as should FRESH's state-funded colleagues at Smokefree South West. The recently formed Give Up Loving Pop (GULP) must also be on thin ice. There are others, of course.

It is probably too much to hope that the rinky-dink governments of Scotland and Wales will stop throwing money at the likes of Alcohol Focus Scotland and Alcohol Concern, but England is certainly ready to save a few million quid by burning some leaches off the taxpayers' skin.

It can't happen a day too soon.

You may recall DrinkWise as the Department of Health front group that used public money to campaign for alcohol advertising bans and minimum unit pricing (MUP). For the latter, they set up a sock-puppet website - anonymously, at first - which made the ludicrous claim that MUP would reduce the price of some drinks. The rest of its campaign literature had a similarly uneasy relationship with the truth.

There is no doubt that DrinkWise were a lobby group (how nice it is to speak of them in the past tense). It's difficult to find any part of their website that was not devoted to encouraging people to 'join the movement', 'act now' or 'write to your MP'. Despite being 100 per cent state-funded, they were proudly and openly engaged in political campaigning.

Since most of their income came from local authorities, they would have been in breach of the Department for Communities and Local Government's new 'anti-sockpuppet clause' which states:

The following costs are not eligible expenditure: payments that support activity intended to influence or attempt to influence Parliament, government or political parties, or attempting to influence the awarding or renewal of contracts and grants, or attempting to influence legislative or regulatory action.

Presumably this was a large part of the reason for its funding being withdrawn. We must also presume that DrinkWise's counterpart across the Pennines, Balance North East, will soon also be consigned to the dustbin of history. Balance North East's room-mates at FRESH should be heading for the door shortly afterwards, as should FRESH's state-funded colleagues at Smokefree South West. The recently formed Give Up Loving Pop (GULP) must also be on thin ice. There are others, of course.

It is probably too much to hope that the rinky-dink governments of Scotland and Wales will stop throwing money at the likes of Alcohol Focus Scotland and Alcohol Concern, but England is certainly ready to save a few million quid by burning some leaches off the taxpayers' skin.

It can't happen a day too soon.

Monday 27 July 2015

Fortunately, Tesco does not have a monopoly

If the newspapers are to be believed, the people who run Tesco have taken leave of their senses.

Have these people been smoking crack? Do they really think that they will appease the 'public health' racketeers by taking Ribena and Rubicon off the shelves? Why not stop selling sweets, chocolate and fruit juice? Why not stop selling packets of sugar, if that's what the demon ingredient is? Why not stop selling cigarettes and alcohol? Above all - as the 'public health' goons were quick to shout on Twitter - why not stop selling Coca-Cola, Pepsi and Tango, all of which will still be available under the new regime? Tesco has started something it will not be able to finish without closing down several aisles.

Speaking of Twitter, I was expressing my bewilderment on there yesterday when the inevitable zinger arrived...

Obviously that is not my position. Tesco is free to bring in whatever policy it likes and I am free to shop elsewhere. The market can therefore decide whether Tesco's policy is sensible or not.

My house is pretty much equidistant between a Tesco and an Asda. I tend to go to Tesco and I won't be boycotting it on principle but when Ribena is on my shopping list - as it sometimes is - I'm damned if I'm going to Tesco for most of my shopping before going elsewhere for my soft drinks. It will be Asda for me.

Living in a free market obviously does not mean that the government forces supermarkets to sell Ribena, but nor does it mean that customers shouldn't complain when a company unnecessarily restricts choice in a doomed attempt to satisfy insatiable 'public health' quacks. Complaining might not make them change their minds, but ultimately it's their loss if people decide to vote with their feet.

Contrast this with government regulation. When the state does it, you can't go elsewhere because the state has a monopoly. What are you going to do? Emigrate? You can vote in the ballot booth, but people rarely vote on a single issue and your vote is pretty much worthless anyway. You have no choice and the government doesn't care if sales fall.

In summary...

Company stops selling something you like:

Complain. If your complaint has no effect, shop elsewhere and make the company suffer. No skin off your nose.

Government bans something you like:

No point complaining. Suck it up. You suffer, they don't.

The UK's biggest supermarket chain is axing some of the best-selling children's drinks brands as the war on sugar is stepped up in a bid to tackle childhood obesity, according to a new report.

Tesco has revealed that it is to cull an array of added-sugar soft drinks including CCE's Capri-Sun and several varieties of Suntory's Ribena as it revamps its range amid growing concerns over health and obesity.

Have these people been smoking crack? Do they really think that they will appease the 'public health' racketeers by taking Ribena and Rubicon off the shelves? Why not stop selling sweets, chocolate and fruit juice? Why not stop selling packets of sugar, if that's what the demon ingredient is? Why not stop selling cigarettes and alcohol? Above all - as the 'public health' goons were quick to shout on Twitter - why not stop selling Coca-Cola, Pepsi and Tango, all of which will still be available under the new regime? Tesco has started something it will not be able to finish without closing down several aisles.

Speaking of Twitter, I was expressing my bewilderment on there yesterday when the inevitable zinger arrived...

@cjsnowdon so you're all about businesses making voluntary decisions rather than government regulators, unless you don't like the decision?

— Evan Blecher (@evanblecher) July 27, 2015

Obviously that is not my position. Tesco is free to bring in whatever policy it likes and I am free to shop elsewhere. The market can therefore decide whether Tesco's policy is sensible or not.

My house is pretty much equidistant between a Tesco and an Asda. I tend to go to Tesco and I won't be boycotting it on principle but when Ribena is on my shopping list - as it sometimes is - I'm damned if I'm going to Tesco for most of my shopping before going elsewhere for my soft drinks. It will be Asda for me.

Living in a free market obviously does not mean that the government forces supermarkets to sell Ribena, but nor does it mean that customers shouldn't complain when a company unnecessarily restricts choice in a doomed attempt to satisfy insatiable 'public health' quacks. Complaining might not make them change their minds, but ultimately it's their loss if people decide to vote with their feet.

Contrast this with government regulation. When the state does it, you can't go elsewhere because the state has a monopoly. What are you going to do? Emigrate? You can vote in the ballot booth, but people rarely vote on a single issue and your vote is pretty much worthless anyway. You have no choice and the government doesn't care if sales fall.

In summary...

Company stops selling something you like:

Complain. If your complaint has no effect, shop elsewhere and make the company suffer. No skin off your nose.

Government bans something you like:

No point complaining. Suck it up. You suffer, they don't.

The insanity of the 'endgame'

Clive Bates gave an outstanding speech at this year's Global Forum on Nicotine in Warsaw. He discusses the anti-smoking lobby's ludicrous 'endgame' and compares it with policies that might actually reducing smoking without creating massive costs on individuals and society. If you haven't watched the video, do.

Sunday 26 July 2015

"No evidence"

The campaign to ban smoking in prisons is marching on thanks to the ever-gullible Observer newspaper and a sock-puppet pressure group known as the Tobacco Control Collaborating Centre. I've never heard of them and nor has The Observer judging from its description of them as "an organisation called the Tobacco Control Collaborating Centre", but its article contains this gem...

No evidence! Not just a little bit of evidence, but no evidence!

Perhaps Debs has forgotten about the events in Australia that took place only a few weeks ago...

This apparent oversight is typical of ASH's view of evidence. As with the mass closure of pubs after the smoking ban, it didn't happen unless it was written up by a tobakko kontrol mouthpiece and published in one of their favoured pal-reviewed journals like the BMJ or - if all else fails - their in-house comic Tobacco Control.

The fact that these things did happen - and have happened before in Queensland, Canada and the USA - is neither here nor there to the single-issue fanatic. They make their own reality.

Some people would call it lying.

Deborah Arnott, chief executive of charity Action on Smoking and Health, said there was no evidence to support claims that depriving prisoners of tobacco could lead to riots.

No evidence! Not just a little bit of evidence, but no evidence!

Perhaps Debs has forgotten about the events in Australia that took place only a few weeks ago...

Prisoners riot at Melbourne's Ravenhall remand centre over smoking ban

Police armed with tear gas and water cannons were on Tuesday evening still attempting to contain a riot that broke out at a maximum security prison in Victoria earlier in the day, after prisoners became angered by the introduction of a smoking ban.

All staff were evacuated from the prison in Ravenhall, Victoria, after several hundred prisoners rioted.

This apparent oversight is typical of ASH's view of evidence. As with the mass closure of pubs after the smoking ban, it didn't happen unless it was written up by a tobakko kontrol mouthpiece and published in one of their favoured pal-reviewed journals like the BMJ or - if all else fails - their in-house comic Tobacco Control.

The fact that these things did happen - and have happened before in Queensland, Canada and the USA - is neither here nor there to the single-issue fanatic. They make their own reality.

Some people would call it lying.

Friday 24 July 2015

The middle class drink epidemic

With alcohol consumption falling every year for over a decade it is becoming increasingly difficult to sustain the myth that Britain is in the grips of a drinking epidemic, but where there’s a will there’s a way. One method is to focus on whichever group is drinking the most. Even though everybody is drinking less, some people are bound to be drinking more than others and that means scary headlines. Inconveniently for the doom-mongerers, the people who are drinking the most happen to be the middle-aged and middle class. It would be a better story if the heaviest drinkers were the tired, the poor and the huddled masses yearning to breathe free, but the evidence clearly shows that they are the white collar professionals. In Britain, people in the top social class consume an average of 15 units of alcohol per week while people in the lowest social class only consume 10.

And so, after an admittedly slow news day, several national newspapers have led with the story - such as it is - of reasonably wealthy people drinking bottles of wine. Or, as the Daily Mail’s front page put it, the ‘Middle Class Drink Epidemic’. ‘Successful middle classes suffering crisis in alcohol abuse’ was The Times’ front page headline while The Telegraph led with ‘Middle classes most at risk from drinking’.

The hook for all this is a study (in reality, a glorified survey) published in BMJ Open which found that successful, wealthy, middle class people over the age of 50 are more likely to exceed the government’s drinking guidelines than their peers. At this point it is customary to point out that you can exceed the guidelines by drinking a glass, or a glass and a half, of wine a day (for women and men respectively), and that the guidelines themselves were ‘plucked out of the air’ in the 1980s. But even if you take the guidelines seriously, exceeding them does not make you a ‘harmful drinker’ or a ‘problem drinker’, as The Times claims in its report. It makes you a mere ‘hazardous drinker’ which is below both in the ladder of risk.

Getting technical definitions wrong is the least of the problems with the reporting of this story. It is simply wrong to claim, as The Telegraph does, that middle class people are ‘most at risk from drinking’. As a class, it is true that they drink the most, but they do not suffer the greatest alcohol-related harm, not by a long shot. The harm disproportionately falls on lower socio-economic groups and they tend to drink the least.

This is what public health researchers call the Alcohol Harm Paradox. Public health researchers call everything a paradox when reality doesn’t bend to accommodate their theories and so, if boozing fails to kill affluent people despite their supposedly hazardous rates of consumption, it doesn’t demonstrate that the guidelines are worthless - heaven forfend! - it is merely a ‘paradox’ that requires more research (ie. more funding).

Alcohol Research UK published a rather inconclusive study about the paradox earlier this year and I’m told that there is more to come. I hope they get to the bottom of it, but I would be surprised if it comes down to much more than two basic problems:

Firstly, the definition of hazardous and harmful drinking is too broad to accurately capture people who are at serious risk of coming to grief. According to the government, there are over 10,000,000 hazardous drinkers and yet there are only 6,000 alcohol-related deaths each year. An annual death rate of 0.06 per cent does not represent much of a hazard.

Secondly, you cannot assume that an arbitrarily defined group of people is going to produce more death and disease than another group merely because their group average exceeds an arbitrary guideline. Why? Because averages tell you nothing about individuals. Yes, people on low incomes drink less than middle class people on average. They don’t have much money and alcohol is a heavily-taxed luxury, but within this group are some people who not only drink very heavily but also have a propensity for other risk-taking behaviours. It should therefore not be surprising that a disproportionate number of alcohol-related hospital admissions and deaths arise in the group that drinks the least. The fact that lots of other poor people bring the group average down by drinking moderately or abstaining is neither here nor there to the low income alcoholic.

We can discuss the reasons why some people at the bottom of the socio-economic ladder turn to drink - and, indeed, why some people who turn to drink end up at the bottom of the socio-economic ladder - but that is not really the point here. The point is that middle class people are not the most at risk from alcohol-related harm, despite drinking more, as a group, on average. Rates of alcohol-related mortality are many times higher in the lowest socio-economic group than in the highest.

It takes a certain amount of self-delusion to look at a group of unusually healthy people and conclude that they are suffering from an ‘epidemic’, and yet the report in The Times includes this timeless gem from a spokesman for Age UK:

‘Because this group is typically healthier than other parts of the older population, they might not realise that what they are doing is putting their health in danger.’

In other words, they might be the healthiest people but according to our calculations they shouldn’t be and so we’re going to pretend that they’re not.

To be fair, Age UK are only taking their cue from the authors of the BMJ Open study who apparently saw no paradox at all when they wrote that the ‘problem of harmful drinking’ is concentrated amongst ‘people in better health’. We are through the looking-glass here, are we not?

Imagine if the results had been different. Imagine that the people (ie. group) who were most likely to be ‘harmful drinkers’ were found to be in the worst health. In those circumstances, it would surely have been reported as proof that exceeding the drinking guidelines is very bad for you. Instead, the study showed the opposite but the band played on regardless.

Tuesday 21 July 2015

Area man speaks out

I'm supposed to be on holiday this week, but the nanny state never sleeps so I was on Sky News earlier today speaking from my backyard (relatively speaking) in Hove about the proposal to ban smoking in parks and beaches. Deborah Arnott from ASH was on the end of a rather distorted line so I didn't catch everything that was said, but she didn't seem like she really had her heart in it to me. Who can blame her? It is a truly appalling idea on every level.

I should be debating the same issue with Brighton and Hove's director of public health tomorrow on BBC Sussex radio (at around 9.10am). If I can get him to explain what the hell a voluntary ban is, I will let you know.

Anyway, here's the video...

UPDATE

He was a no-show.

I should be debating the same issue with Brighton and Hove's director of public health tomorrow on BBC Sussex radio (at around 9.10am). If I can get him to explain what the hell a voluntary ban is, I will let you know.

Anyway, here's the video...

UPDATE

He was a no-show.

Those sugar guidelines are not what they seem

At The Spectator, I discuss last week's lowering of the sugar 'allowance'. Some people have said they can't access the site if they're using Chrome so here it is in full...

Like putting Dracula in charge of a blood bank’ is how Action on Sugar’s Simon Capewell described Ian MacDonald’s role as chairman of the Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (SACN) last year. Professor MacDonald’s reputation as one of Britain’s leading nutritionists gave him no protection when Channel 4’s Dispatches programme devoted half an hour to attacking any scientist who receives grant funding from the food industry. Seemingly unaware that industry-government partnerships are the norm in diet research, Action on Sugar’s Aseem Malhotra accused MacDonald of being ‘in bed with the food industry’ and called for his resignation. Similar inferences and accusations were made in a British Medical Journal ‘investigation’ earlier this year.

We shall probably never know whether this smear campaign had any influence on the conclusions of the SACN report when it was released last week, but the campaigners certainly got what they wanted when MacDonald et al halved the recommended sugar intake from 10 per cent of daily calories to five per cent. A lower limit has been the holy grail for the anti-sugar movement for years (for reasons I recently discussed). The World Health Organisation let them down earlier this year when it kept the limit at ten per cent, but SACN played ball and the talk of Dracula and blood banks was conspicuous by its absence on Friday morning.

The pool of nutritional epidemiology is murky at the best of times, leading some academics to dismiss the whole field as pseudoscience, but if you are prepared to give it the benefit of the doubt, the SACN report provides a decent summary of the evidence to date. Taken together, it does not make happy reading for the anti-sugar/low-carb movement. SACN found an association, based on ‘moderate evidence’, between sugary drinks and type 2 diabetes, but it failed to support any of the other pet theories of the anti-sugar campaigners. For example, it found ‘no association’ between sugar and type 2 diabetes, ‘no association’ between sugar and blood insulin, and ‘no association’ between sugary drinks and childhood obesity. It also found no association between fructose (the bête noire of the anti-sugar lobby) and type 2 diabetes. As for the low-carb diet, SACN found ‘no association between total carbohydrate intake and body mass index or body fatness’, nor with type 2 diabetes or cardiovascular disease. By contrast, it found ‘some evidence that an energy restricted, higher carbohydrate, lower fat diet may be an effective strategy for reducing body mass index and body weight.’

You need to reach page 183 to find the only part of the 370-page report that made the headlines. SACN explained its decision to recommend reducing sugar consumption to five per cent of daily energy as follows:

‘To quantify the dietary recommendation for sugars, advice from the Calorie Reduction Expert Group was considered. It was estimated that a 418 kJ/person/day (100kcal/person/day) reduction in energy intake of the population would address energy imbalance and lead to a moderate degree of weight loss in the majority of individuals (Calorie Reduction Expert Group, 2011) … To achieve an average reduction in energy intakes of 418 kJ (100kcal/person/day) using this estimated effect size, intake of free sugars would need to be reduced by approximately five per cent of total dietary energy (418kJ/78kJ= 5.4) … A five percentage point reduction in energy from the current dietary recommendation for sugars would mean that the population average of free sugars should not exceed five per cent of total dietary energy.’

In other words, the average person consumes too many calories and if sugar consumption was reduced from 10 per cent of energy to five per cent of energy, people would eat 100 fewer calories (unless, of course, they compensated by eating more calories from other sources). This is the sole justification in the SACN report for changing the guidance on sugar. The mathematics is correct – 100 calories is roughly five per cent of an adult’s recommended intake. The logic is not wrong, it is merely trivial. If the aim of dietary advice is to get people to eat 100 fewer calories a day, similar edicts could be announced about any ingredient or food. Telling people to eat 25 fewer grammes of cheese a day would serve exactly the same purpose, but it would not tell us how much cheese it is safe to eat.

There is no difference whatsoever between saying ‘eat 100 fewer calories’ and ‘reduce your sugar consumption from 14 teaspoons a day to 7 teaspoons’. The latter, which has now been enshrined in official guidance, is merely one way of achieving the former. It is doubtful that even one person in 100 who saw last week’s headlines realises this. It is much more likely that they think scientists have found new evidence showing that consuming more than seven teaspoons a day is inherently dangerous, even toxic.

The clear implication from the new daily ‘allowance’ is that it represents the upper limit of a risk threshold, above which it is dangerous to stray. This is not what the SACN report says, and it is not their justification for changing their guidance, but it will be portrayed as the ‘safe limit’ by pressure groups forever more.

Like putting Dracula in charge of a blood bank’ is how Action on Sugar’s Simon Capewell described Ian MacDonald’s role as chairman of the Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (SACN) last year. Professor MacDonald’s reputation as one of Britain’s leading nutritionists gave him no protection when Channel 4’s Dispatches programme devoted half an hour to attacking any scientist who receives grant funding from the food industry. Seemingly unaware that industry-government partnerships are the norm in diet research, Action on Sugar’s Aseem Malhotra accused MacDonald of being ‘in bed with the food industry’ and called for his resignation. Similar inferences and accusations were made in a British Medical Journal ‘investigation’ earlier this year.

We shall probably never know whether this smear campaign had any influence on the conclusions of the SACN report when it was released last week, but the campaigners certainly got what they wanted when MacDonald et al halved the recommended sugar intake from 10 per cent of daily calories to five per cent. A lower limit has been the holy grail for the anti-sugar movement for years (for reasons I recently discussed). The World Health Organisation let them down earlier this year when it kept the limit at ten per cent, but SACN played ball and the talk of Dracula and blood banks was conspicuous by its absence on Friday morning.

The pool of nutritional epidemiology is murky at the best of times, leading some academics to dismiss the whole field as pseudoscience, but if you are prepared to give it the benefit of the doubt, the SACN report provides a decent summary of the evidence to date. Taken together, it does not make happy reading for the anti-sugar/low-carb movement. SACN found an association, based on ‘moderate evidence’, between sugary drinks and type 2 diabetes, but it failed to support any of the other pet theories of the anti-sugar campaigners. For example, it found ‘no association’ between sugar and type 2 diabetes, ‘no association’ between sugar and blood insulin, and ‘no association’ between sugary drinks and childhood obesity. It also found no association between fructose (the bête noire of the anti-sugar lobby) and type 2 diabetes. As for the low-carb diet, SACN found ‘no association between total carbohydrate intake and body mass index or body fatness’, nor with type 2 diabetes or cardiovascular disease. By contrast, it found ‘some evidence that an energy restricted, higher carbohydrate, lower fat diet may be an effective strategy for reducing body mass index and body weight.’

You need to reach page 183 to find the only part of the 370-page report that made the headlines. SACN explained its decision to recommend reducing sugar consumption to five per cent of daily energy as follows:

‘To quantify the dietary recommendation for sugars, advice from the Calorie Reduction Expert Group was considered. It was estimated that a 418 kJ/person/day (100kcal/person/day) reduction in energy intake of the population would address energy imbalance and lead to a moderate degree of weight loss in the majority of individuals (Calorie Reduction Expert Group, 2011) … To achieve an average reduction in energy intakes of 418 kJ (100kcal/person/day) using this estimated effect size, intake of free sugars would need to be reduced by approximately five per cent of total dietary energy (418kJ/78kJ= 5.4) … A five percentage point reduction in energy from the current dietary recommendation for sugars would mean that the population average of free sugars should not exceed five per cent of total dietary energy.’

In other words, the average person consumes too many calories and if sugar consumption was reduced from 10 per cent of energy to five per cent of energy, people would eat 100 fewer calories (unless, of course, they compensated by eating more calories from other sources). This is the sole justification in the SACN report for changing the guidance on sugar. The mathematics is correct – 100 calories is roughly five per cent of an adult’s recommended intake. The logic is not wrong, it is merely trivial. If the aim of dietary advice is to get people to eat 100 fewer calories a day, similar edicts could be announced about any ingredient or food. Telling people to eat 25 fewer grammes of cheese a day would serve exactly the same purpose, but it would not tell us how much cheese it is safe to eat.

There is no difference whatsoever between saying ‘eat 100 fewer calories’ and ‘reduce your sugar consumption from 14 teaspoons a day to 7 teaspoons’. The latter, which has now been enshrined in official guidance, is merely one way of achieving the former. It is doubtful that even one person in 100 who saw last week’s headlines realises this. It is much more likely that they think scientists have found new evidence showing that consuming more than seven teaspoons a day is inherently dangerous, even toxic.

The clear implication from the new daily ‘allowance’ is that it represents the upper limit of a risk threshold, above which it is dangerous to stray. This is not what the SACN report says, and it is not their justification for changing their guidance, but it will be portrayed as the ‘safe limit’ by pressure groups forever more.

Monday 20 July 2015

Why I no longer live in Brighton

From 12 July 2015...

Injecting in daylight: the plight of our parks

A man was photographed injecting drugs at a park where residents say it happens on a daily basis.

A concerned passer-by snapped a picture in Peace Park, off Dorset Gardens, of someone using a needle before 10am in the morning.

... Residents in the Brighton street said they were not surprised, as drug use is becoming more commonplace in an ongoing and longstanding problem in the city’s parks.

With needles found frequently in Peace Park, littering the bushes and undergrowth, the council acknowledge drug abuse was a “significant issue” for Brighton and Hove.

Three days later...

Potential smoking ban for Brighton and Hove beaches and parks

A smoking ban could be introduced on beaches and in parks across Brighton and Hove.

Plans have been drawn up to hold a consultation asking whether people support a move to extend smoke-free areas across the city.

The aim is to try to create an environment free from second hand smoke, which is particularly dangerous for children.

Truly, the San Francisco of England. In the worst possible way.

As usual, the Daily Mash gets it right.

Sunday 19 July 2015

We need more people like Graham MacGregor

Graham MacGregor, the chair of Action on Sugar, has been speaking to the newspapers again. This can only be a good thing for those of us who want to see the 'public health' racket discredited and destroyed. MacGregor performs a valuable service with his swivel-eyed rhetoric and transparent lies. Just as it is useful to have inept British Medical Association spokespeople talking obvious rubbish about e-cigarettes, so it is important that unhinged fanatics like MacGregor be given enough rope.

Here he is talking to The Observer today...

Nurse!

This is bollocks, as I have explained before.

It's only a surprise if you ignore individual responsibility, self-determination and choice. To a reasonable person, the fact that three-quarters of us are not obese demonstrates that people's health is not determined by the 'obesogenic environment' and 'Big Food'.

NURSE!

I'm not and I assume MacGregor isn't either.

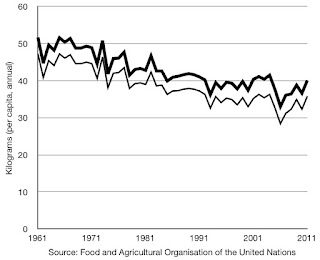

This may be true. Certainly, people underestimate what they eat and drink, but the fact remains that sugar consumption has been falling for years regardless of whether you look at what people say they eat or how much is sold. The graph below shows how much is sold in Britain - the thick line is all sugars, the thin line is refined sugar.

He continues...

If you read the whole article, you'll see that this is not true. It quotes a food scientist saying that reducing sugar is "quite a challenge". This is a coy understatement. The article notes that "experiments have shown consistently that products which replace sugar with other sweeteners are coming up constantly as having an “artificial” and “chemical” taste. “Mouth drying” and “bitter” are other frequently used words". In other words, the food tastes awful and people won't buy it.

This is the catch-all lie used by single-issue health campaigners of every stripe. Aside from the simple fact that a state-run health service cannot go bankrupt, the evidence shows that reducing obesity will increase, not reduce, healthcare costs.

Notice the none-too-subtle switch from talking about sugar to talking about diabetes, as if the costs of diabetes - including type 1 diabetes, which is not related to obesity at all - were the costs of sugar consumption.

I've never heard this ludicrous claim before. I can only assume he has made it up on the spot.

NURSE!!!

As the article explains, this is a total fantasy.

Keep up the good work, Graham.

Here he is talking to The Observer today...

Sugar is the deadliest threat facing Britain today, and yet it is all but ignored by politicians and sold in every town across the country, said Graham MacGregor, professor of cardiovascular medicine at the Wolfson Institute, Queen Mary College, University of London, and chairman of the health pressure group Action on Sugar, which wants urgent government action.“The socially deprived and children are being targeted heavily by very clever people and it’s a disgrace. Fast-food outlets are in socially deprived areas and every one is selling fat, sugar and death."“But it’s not just the socially deprived,” MacGregor added. “There are all these TV chefs – their food is not much better."

Nurse!

“People haven’t twigged that the biggest cause of death is what we’re eating."

This is bollocks, as I have explained before.

"It’s no surprise that we’re so obese; the biggest surprise is why aren’t we all obese."

It's only a surprise if you ignore individual responsibility, self-determination and choice. To a reasonable person, the fact that three-quarters of us are not obese demonstrates that people's health is not determined by the 'obesogenic environment' and 'Big Food'.

"We’re all being slowly poisoned."

NURSE!

"We’re all eating too much sugar..."

I'm not and I assume MacGregor isn't either.

"...people grossly underestimate how much they consume. We know that because in surveys, if you ask people how much fizzy drink they consume, you get a figure two-and-a-half times less than how much is being sold.”

This may be true. Certainly, people underestimate what they eat and drink, but the fact remains that sugar consumption has been falling for years regardless of whether you look at what people say they eat or how much is sold. The graph below shows how much is sold in Britain - the thick line is all sugars, the thin line is refined sugar.

He continues...

“We’ve been very successful in reducing salt. It’s gone down by 30-40% and nobody’s noticed. That was because there was the political will in the Labour government. We can easily do the same thing for sugar and fat."

If you read the whole article, you'll see that this is not true. It quotes a food scientist saying that reducing sugar is "quite a challenge". This is a coy understatement. The article notes that "experiments have shown consistently that products which replace sugar with other sweeteners are coming up constantly as having an “artificial” and “chemical” taste. “Mouth drying” and “bitter” are other frequently used words". In other words, the food tastes awful and people won't buy it.

"And without it, frankly, we’re looking at a bankrupt NHS."

This is the catch-all lie used by single-issue health campaigners of every stripe. Aside from the simple fact that a state-run health service cannot go bankrupt, the evidence shows that reducing obesity will increase, not reduce, healthcare costs.

"Diabetes already costs the NHS £10bn a year and is set to go to £30bn by 2020."

Notice the none-too-subtle switch from talking about sugar to talking about diabetes, as if the costs of diabetes - including type 1 diabetes, which is not related to obesity at all - were the costs of sugar consumption.

"It will eat half the NHS budget."

I've never heard this ludicrous claim before. I can only assume he has made it up on the spot.

“The food industry walks all over us. It is seen as untouchable"

NURSE!!!

"The government knows it can enforce [change] if it wants to. We did it with tobacco; you can easily take out up to 50% of the sugar without anybody noticing, if you do it slowly.”

As the article explains, this is a total fantasy.

Keep up the good work, Graham.

Saturday 18 July 2015

Sugar and the mythical past

Via Simon Capewell's deranged Twitter feed, I have come across a blog post entitled 'Obesity is the new plague' which demands a 100 per cent sugar tax. It is typical of its genre in complaining that modern food companies 'spike' good old-fashioned British cuisine with needless sugar. The author gives an interesting example...

Sugar is naturally occurring in mint, of course, but it is true that companies usually add refined sugar to make mint sauce.

When did this devious practice of stuffing good, honest mint sauce with sugar take hold? The BBC's recipe for mint sauce recommends a level tablespoon of caster sugar, so the practice is clearly not confined to 'Big Food', but let's go further back and consult Mrs Beeton's famous Book of Household Management, published in 1859. Her recipe was as follows:

That's rather a lot of sugar, isn't it, if you don't know anything about cooking? And it comes from a recipe book published 156 years ago that is a cornerstone of our knowledge about 'traditional food'. If you look through volume one of Mrs Beeton's tome (it's open access), you will see sugar being used very liberally, and not just in desserts like custard (3 ounces of powdered sugar), but in most of her soups, sauces and stocks as well as her recipes for salad dressing, baked carp, chutney, spiced beef, beef pickle, cucumber preserve, etc. etc.

Trying to reason with anti-sugar fanatics is probably futile, but they really should come to terms with the fact that sugar is not some radical new ingredient that has suddenly been poured into the food supply in the last thirty years. As I have mentioned before, the best estimates of historical sugar consumption show that the average Briton was consuming 90 pounds of sugar in 1901, whereas the average Briton today consumes something in the region of 75 pounds of sugar.

You have to go back a very long way - ie. several centuries - if you want to find cooking without sugar in it. Perhaps it is the goal of the anti-sugar wingnuts to take us back to a pre-Industrial Revolution diet that really was tasteless (notwithstanding all the salt and alcohol). Or maybe they just don't understand how basic dishes have been cooked for generations.

Cooking classes are often recommended as a way to tackle obesity, but it may be the anti-obesity crusaders who are most in need of them. Perhaps if they got used to dealing with sugar in tablespoons and cups rather than in measly teaspoons, they might come to their senses. They could start by making one of Jamie Oliver's cakes.

Sugar is everywhere ... even in mint sauce – I always thought that contained mint and vinegar... Do we NEED it so much, is our traditional food so tasteless?

Sugar is naturally occurring in mint, of course, but it is true that companies usually add refined sugar to make mint sauce.

When did this devious practice of stuffing good, honest mint sauce with sugar take hold? The BBC's recipe for mint sauce recommends a level tablespoon of caster sugar, so the practice is clearly not confined to 'Big Food', but let's go further back and consult Mrs Beeton's famous Book of Household Management, published in 1859. Her recipe was as follows:

MINT SAUCE, to serve with Roast Lamb.

INGREDIENTS.—4 dessertspoonfuls of chopped mint, 2 dessertspoonfuls of pounded white sugar, 1/4 pint of vinegar.

That's rather a lot of sugar, isn't it, if you don't know anything about cooking? And it comes from a recipe book published 156 years ago that is a cornerstone of our knowledge about 'traditional food'. If you look through volume one of Mrs Beeton's tome (it's open access), you will see sugar being used very liberally, and not just in desserts like custard (3 ounces of powdered sugar), but in most of her soups, sauces and stocks as well as her recipes for salad dressing, baked carp, chutney, spiced beef, beef pickle, cucumber preserve, etc. etc.

Trying to reason with anti-sugar fanatics is probably futile, but they really should come to terms with the fact that sugar is not some radical new ingredient that has suddenly been poured into the food supply in the last thirty years. As I have mentioned before, the best estimates of historical sugar consumption show that the average Briton was consuming 90 pounds of sugar in 1901, whereas the average Briton today consumes something in the region of 75 pounds of sugar.

You have to go back a very long way - ie. several centuries - if you want to find cooking without sugar in it. Perhaps it is the goal of the anti-sugar wingnuts to take us back to a pre-Industrial Revolution diet that really was tasteless (notwithstanding all the salt and alcohol). Or maybe they just don't understand how basic dishes have been cooked for generations.

Cooking classes are often recommended as a way to tackle obesity, but it may be the anti-obesity crusaders who are most in need of them. Perhaps if they got used to dealing with sugar in tablespoons and cups rather than in measly teaspoons, they might come to their senses. They could start by making one of Jamie Oliver's cakes.

Friday 17 July 2015

Sweet Truth

It's been a week of sugar, starting with the deeply misleading article on the front of the Sunday Times and culminating in the SACN report today. I'll say more about the latter next week, suffice it to say that its conclusions do not follow from the evidence.

It was a good (or possible bad) week for the Institute of Economic Affairs to release a new report on sugar which Rob Lyons and myself have been working on since the start of the year. It asks a question that is shamefully not being asked in all the hullabaloo about what the ideal amount of sugar to eat might be, ie. whether the government should be getting involved at all.

Specifically we find that:

- Consumers are reasonably well informed about the hazards of eating too much sugar in terms of obesity, diabetes and tooth decay. The vast majority of food is adequately labelled.

- Consumers have an enormous amount of choice, 'food deserts' don't exist in the UK, and low-sugar options are readily available to those who want them

- There are no significant negative externalities associated with obesity, but even if external costs existed they would be the result of caloric food and drinks in general, plus physical inactivity. There is no reason to single sugar out.

In short, there is no market failure for the government to (attempt to) correct. Moreover, the solutions proposed by Action on Sugar are seriously flawed. For example...

- A ban on television advertising for foods that are high in fat, salt or sugar (HFSS) before 9pm would effectively confine the promotion of a huge number of products, including cheese, bacon, cakes and biscuits, to a few hours late at night. Such a ban would have a detrimental effect on programming and would restrict useful commercial information.

- Limiting the availability of fast food outlets stifles competition, favours incumbents, and distorts the market by preventing supply meeting demand. It is therefore likely to result in higher prices and poorer quality.

- Taxes on food and soft drinks have been shown to be ineffective in reducing obesity due to inelastic demand and substitution effects. The cost to the taxpayer far exceeds any savings that might be made and the highest burden would fall on low income consumers.

If you're at all interested in the current sugar debate, I recommend you download Sweet Truth for free here and read it.

Tuesday 14 July 2015

Britain's tooth decay 'crisis'

‘Rotten teeth in toddlers at crisis level’ was the front page headline of The Sunday Times this week, leading to a predictable call for tobacco-style regulation of food. The story was based on quotes from Nigel Hunt of the Royal College of Surgeons who wants graphic photos of rotten teeth to be placed on sweets and fizzy drinks.

It is difficult to hear the claim that tooth decay in Britain is ‘reaching crisis point’ without assuming that things have been getting worse and are now verging on the catastrophic. That is surely the intention of such rhetoric but it is simply not true. Far from getting worse, rates of tooth decay have been declining at a sharp rate in Britain for several decades. In the BBC’s coverage of Hunt’s remarks, the Department of Health conceded that ‘Children’s teeth are dramatically healthier than they were 10 years ago’, though it accepts that there is still room for improvement.

Why settle for the last ten years? According to a report by the Royal College of Surgeons - Professor Hunt’s own organisation - ‘oral health has improved significantly since the 1970s’. Does that include children? You betcha. ‘The dental health of the majority of British children has improved dramatically since the early 1970s,’ according to a 2005 study, mainly because of ‘the widespread availability of fluoride containing toothpastes’. This was confirmed in a 2011 study which concluded that ‘since the 1970s, the oral health of the population, both children's dental decay experience and the decline [in] adult tooth loss, has improved steadily and substantially.’

Figures from the Office for National Statistics show that the number of 12 year olds who exhibited clear signs of tooth decay fell from 81 per cent in 1983 to 28 per cent in 2013 - a remarkable decline by any standard. In Scotland, the rate amongst four year olds nearly halved from 62 per cent in 1994 to 32 per cent in 2014. Rates of tooth decay are not just lower than they were in past, they are low by the standards of nearly any other country, with the aforementioned 2005 study finding that ‘levels of dental decay in UK children at 5 and 12 years are amongst the lowest in the world.’

Crisis? What crisis? If one reads The Sunday Times article carefully, it becomes clear that the real problem is the healthcare system. The basis of Hunt’s complaint is that some children are having to wait months before they can have teeth extracted under general anaesthetic in a hospital. This is a disgrace, but it is not due to an epidemic of tooth decay so much as the endemic incompetence and inefficiency in the NHS money pit. As a nation, we have been dutifully brushing our teeth and have reaped the rewards through markedly better dental health, fewer cavities and fewer fillings, but this is not enough for the mandarins of the NHS. The healthcare system cannot live up to its ludicrous billing as The Envy of the World and so, as with all failing socialist projects, scapegoats must be found.

As Douglas Murray observed in The Spectator last month, victim-blaming has become the medical establishment’s default response to its own failures. The shrill demands for government action are a crude diversionary tactic. Can’t get the waiting lists down? Bring in a sugar tax! Unable to carry out minor operations? Put graphic warnings on Mars bars! It is a shameless distraction from the real issue, but when combined with the media’s gross misrepresentation of the facts and the political class’s thirst for legislation, it is a pretty effective one.

It is difficult to hear the claim that tooth decay in Britain is ‘reaching crisis point’ without assuming that things have been getting worse and are now verging on the catastrophic. That is surely the intention of such rhetoric but it is simply not true. Far from getting worse, rates of tooth decay have been declining at a sharp rate in Britain for several decades. In the BBC’s coverage of Hunt’s remarks, the Department of Health conceded that ‘Children’s teeth are dramatically healthier than they were 10 years ago’, though it accepts that there is still room for improvement.

Why settle for the last ten years? According to a report by the Royal College of Surgeons - Professor Hunt’s own organisation - ‘oral health has improved significantly since the 1970s’. Does that include children? You betcha. ‘The dental health of the majority of British children has improved dramatically since the early 1970s,’ according to a 2005 study, mainly because of ‘the widespread availability of fluoride containing toothpastes’. This was confirmed in a 2011 study which concluded that ‘since the 1970s, the oral health of the population, both children's dental decay experience and the decline [in] adult tooth loss, has improved steadily and substantially.’

Figures from the Office for National Statistics show that the number of 12 year olds who exhibited clear signs of tooth decay fell from 81 per cent in 1983 to 28 per cent in 2013 - a remarkable decline by any standard. In Scotland, the rate amongst four year olds nearly halved from 62 per cent in 1994 to 32 per cent in 2014. Rates of tooth decay are not just lower than they were in past, they are low by the standards of nearly any other country, with the aforementioned 2005 study finding that ‘levels of dental decay in UK children at 5 and 12 years are amongst the lowest in the world.’

Crisis? What crisis? If one reads The Sunday Times article carefully, it becomes clear that the real problem is the healthcare system. The basis of Hunt’s complaint is that some children are having to wait months before they can have teeth extracted under general anaesthetic in a hospital. This is a disgrace, but it is not due to an epidemic of tooth decay so much as the endemic incompetence and inefficiency in the NHS money pit. As a nation, we have been dutifully brushing our teeth and have reaped the rewards through markedly better dental health, fewer cavities and fewer fillings, but this is not enough for the mandarins of the NHS. The healthcare system cannot live up to its ludicrous billing as The Envy of the World and so, as with all failing socialist projects, scapegoats must be found.

As Douglas Murray observed in The Spectator last month, victim-blaming has become the medical establishment’s default response to its own failures. The shrill demands for government action are a crude diversionary tactic. Can’t get the waiting lists down? Bring in a sugar tax! Unable to carry out minor operations? Put graphic warnings on Mars bars! It is a shameless distraction from the real issue, but when combined with the media’s gross misrepresentation of the facts and the political class’s thirst for legislation, it is a pretty effective one.

Monday 13 July 2015

Meddlers gonna meddle

The tiresome British Meddling Association have published a pamphlet (or a 'major report' if you are the BBC) calling for a 20 per cent tax on fizzy drinks and many other horrendous policies.

You can read the whole thing here if you have a strong stomach. Note that the BMA explicitly views a fizzy drinks tax as 'a useful first step' but says that 'taxing a wide range of products is an important long-term goal.'

The BMA don't mention that their soda tax will cost the public £1 billion a year, nor do they acknowledge that it would be deeply regressive. Indeed, they want to make it more even more regressive by taxing fizzy drinks (which are disproportionately purchased by people on low incomes) and use the money to subsidise fruit and vegetables (which are disproportionately purchased by people on high incomes). Nice.

In the pages of The Guardian, their spokeswoman, Sheila Hollins, resorts to flat out lying...

Hollins is the BMA's chair of the board of science so must be aware of the evidence from countries that have experimented with taxes on food and drinks, including Denmark (which is also strangely absent from the pamphlet). The evidence on sugary drinks, in particular, is consistent in finding little, if any, change in patterns of consumption and no change at all in 'health outcomes', including obesity (see here and here for a summary).

You can read the whole thing here if you have a strong stomach. Note that the BMA explicitly views a fizzy drinks tax as 'a useful first step' but says that 'taxing a wide range of products is an important long-term goal.'

The BMA don't mention that their soda tax will cost the public £1 billion a year, nor do they acknowledge that it would be deeply regressive. Indeed, they want to make it more even more regressive by taxing fizzy drinks (which are disproportionately purchased by people on low incomes) and use the money to subsidise fruit and vegetables (which are disproportionately purchased by people on high incomes). Nice.

In the pages of The Guardian, their spokeswoman, Sheila Hollins, resorts to flat out lying...

“We know from experiences in other countries that taxation on unhealthy food and drinks can improve health outcomes, and the strongest evidence of effectiveness is for a tax on sugar-sweetened beverages."

Hollins is the BMA's chair of the board of science so must be aware of the evidence from countries that have experimented with taxes on food and drinks, including Denmark (which is also strangely absent from the pamphlet). The evidence on sugary drinks, in particular, is consistent in finding little, if any, change in patterns of consumption and no change at all in 'health outcomes', including obesity (see here and here for a summary).

The state vs. the market

Last week, the government of New South Wales banned smoking in outdoor dining areas because, er, it felt like it. Proprietors have reacted in a predictable way to minimise the economic damage...

Ladies and gentlemen, I give you the dead hand of the state.

@TenNewsSydney a lot of places are just banning eating outside and letting the smoking continue pic.twitter.com/VAiQ4XgrcN

— andrew reed (@andrewreeeeeeed) July 10, 2015

Ladies and gentlemen, I give you the dead hand of the state.

Sunday 12 July 2015

Smoking ban wrecks businesses, as usual

The year's least surprising news, via the Australian Daily Telegraph...

It's the same story all over the world whether the ban is indoor or out. If smoking bans were good for business, as the anti-smoking liars claim, businesses wouldn't need to be forced by the state to impose them. And 'forced' is very much the word when owners are compelled to act as policemen under threat of penalties that are vastly disproportionate to the 'crime'.

$5,500 is about £2,600. £2,600 for failing to stop somebody smoking outside your building, FFS.

No doubt the charlatans of 'public health' are already writing a study showing that outdoor smoking bans increase revenues in the hospitality industry and lead to dramatic declines in heart attacks.

Worried cafe owners hit by new outdoor smoking bans are watching their profits, and their patrons, disappear in a final puff of smoke.

Some report trade has more than halved since the introduction last Monday of laws banning smoking in outdoor dining areas in pubs, clubs, cafes and restaurants, or within four metres of them.

Among the hardest hit are shisha bars popular in areas like Parramatta, Lakemba and Burwood, where customers traditionally smoke water pipes, commonly known as hookahs or hubbly bubbly.

“This has buried my whole business,” said [name removed at his request in 2019 - CJS], owner of the [business that is now completely closed - CJS 2019] in Church St, Parramatta.

“Sixty per cent of my customers have walked out the door."

... “My coffee trade is down 30 per cent, and I’m not the only one suffering,” Vivo cafe on George Street owner Angela Vithoulkas, who is also a Sydney City Councillor, said.

“I have lost hundreds of coffee visits. Many regulars didn’t even bother turning up on Monday — they’re gone.”

It's the same story all over the world whether the ban is indoor or out. If smoking bans were good for business, as the anti-smoking liars claim, businesses wouldn't need to be forced by the state to impose them. And 'forced' is very much the word when owners are compelled to act as policemen under threat of penalties that are vastly disproportionate to the 'crime'.

NSW Health inspectors were on patrol across the state last week with the power to issue on-the-spot fines of $300 for individuals and $5,500 for occupiers who ignored the ban.

$5,500 is about £2,600. £2,600 for failing to stop somebody smoking outside your building, FFS.

No doubt the charlatans of 'public health' are already writing a study showing that outdoor smoking bans increase revenues in the hospitality industry and lead to dramatic declines in heart attacks.

Friday 10 July 2015

Fizzed out

The New Zealand Taxpayers Union have published a snappy report about sugar and fizzy drink taxes which is worth a read. It includes some new data about the soda tax in Mexico and a foreword by yours truly. The foreword reads:

Download it here.

If you regularly consume more calories than you expend, you will get fat. This is a simple truism, but beneath it lies a web of complexity. There are thousands of food products and thousands of ways to be physically active. People live under different circumstances, in different environments and have different tastes. It would be absurd to blame a single ingredient, let alone a single product category, for the rise in obesity that has been witnessed around the world. Nevertheless, that is what single issue pressure groups like FIZZ have sought to do. This excellent report shows why their campaign to use tax as a weapon against sugar is dangerous nonsense.

The shipwreck of the Danish fat tax should be the world’s lighthouse in regard to health-related taxes on food and drink. All the unintended consequences associated with them were on display in the fifteen months of this ill-fated experiment. The impact on fat consumption was trivial and the effect on obesity was non-existent. Danish consumers switched to cheaper brands of the same products and bought them from cheaper stores, sometimes in cheaper countries. Inflation rose, jobs were lost and people on low incomes suffered most severely from the rising cost of living. Little wonder, then, that the tax was swiftly repealed by an overwhelming majority in the Danish parliament in 2012.

There are important lessons here but if the ‘public health’ lobby has learned them it is only so they can repeat them exactly, this time with sugar. There is no reason to expect a different outcome.

As numerous studies have shown, people tend to be flexible in how much they are prepared to pay for the food and drink they enjoy. They would sooner make sacrifices in other areas of the household budget than change their eating habits. The Danish experience is not unique in demonstrating this. The evidence from the USA, where a number of states have introduced soda taxes, tells the same story.

Faced with a dismal record of failure in the real world, campaigners for food and drink taxes have retreated into a world of statistical models in order to prove that policies which don’t work in practice can be made to work in theory. But there is no running away from the facts outlined in this report. Taxing fat, sugar or soda is an effective method of raising government revenue precisely because people keep on buying them.

A sugar tax is attractive to politicians because it allows them to engage in mass pick-pocketing with a sense of moral superiority. They need to be reminded that there is nothing moral about introducing a regressive stealth tax when you know that demand is inelastic. Taxing food and drink won’t make the poor healthier, but it will certainly help to ensure they stay poor.

It is not good enough to say that anything is worth a try in the campaign against obesity. A policy that is known to incur significant costs without reaping any measurable rewards is a policy that should be rejected without a second thought.

Download it here.

Thursday 9 July 2015

Misunderstanding advertising

My latest post for Spectator Health is about 'public health' people hating advertising because they don't understand it.

Do have a read.

In response to drinks companies saying that advertising doesn’t increase overall sales, Alcohol Action’s response is: ‘Alcohol sponsorship of sport works in terms of increasing sales and, as a result, alcohol consumption. If it didn’t, the alcohol industry simply would not spend so much money on it.’To see how silly this claim is, forget about alcohol for a moment and consider products such as cat food and toilet paper. These products are advertised quite heavily despite there being an obvious ceiling on how much can be consumed. If someone were to say ‘Cat food advertising works in terms of increasing sales and, as a result, cat food consumption. If it didn’t, the pet industry simply would not spend so much money on it’, I hope you would question their sanity. It is quite obvious that Whiskas adverts are designed to lure Felix customers over to their brand. Their commercials could only increase overall consumption if they encouraged people to buy more cats, which is fairly unlikely.

Do have a read.

Food control

Wednesday 8 July 2015

When the levy breaks

Slipped away in George Osborne's budget today was some news on the tobacco levy. This is the looting that ASH wants the government to do in order to keep itself in business. Via the FT...

Feel free to contradict me in the comments, but my understanding of the issue is this:

ASH's original idea was to have a literal levy, like a windfall tax or the Master Settlement Agreement, in which companies would have a certain proportion of their profits taken from them by the government.

This was never practical because the British government has no authority to take profits from companies based abroad (eg. JTI and PMI) and the companies that are still based in UK (BAT and Imperial) would be sorely tempted to up sticks if such a levy came in.

In the last budget statement, the government noted that its public consultation had identified some problems with the idea of a levy. By the time I was debating this on the radio a few weeks ago, ASH seemed to have come to terms with the fact that it was impractical. Instead, they were arguing that an additional tax be placed on tobacco, the proceeds of which would be ear-marked for anti-smoking initiatives, ie. for them and their mates.

This amounts to no more than an additional sin tax on tobacco, with the usual negative impact on the poor and on the black market. Since tobacco duty is already due to rise above inflation, with the money going towards general government expenditure rather than prohibitionist pressure groups, the government has decided to call the whole thing off.

Good. Now the government needs to stop funding ASH entirely.

The impact of a tobacco levy on the tobacco market would be similar to a duty rise, with tobacco manufacturers and importers passing the levy onto consumer prices.

As tobacco duties have already increased this year and will continue to increase by more than inflation each year in this Parliament, the government has decided not to introduce a levy on tobacco manufacturers and importers

Feel free to contradict me in the comments, but my understanding of the issue is this:

ASH's original idea was to have a literal levy, like a windfall tax or the Master Settlement Agreement, in which companies would have a certain proportion of their profits taken from them by the government.

This was never practical because the British government has no authority to take profits from companies based abroad (eg. JTI and PMI) and the companies that are still based in UK (BAT and Imperial) would be sorely tempted to up sticks if such a levy came in.

In the last budget statement, the government noted that its public consultation had identified some problems with the idea of a levy. By the time I was debating this on the radio a few weeks ago, ASH seemed to have come to terms with the fact that it was impractical. Instead, they were arguing that an additional tax be placed on tobacco, the proceeds of which would be ear-marked for anti-smoking initiatives, ie. for them and their mates.

This amounts to no more than an additional sin tax on tobacco, with the usual negative impact on the poor and on the black market. Since tobacco duty is already due to rise above inflation, with the money going towards general government expenditure rather than prohibitionist pressure groups, the government has decided to call the whole thing off.

Good. Now the government needs to stop funding ASH entirely.

That dramatic proliferation in betting shops (slight return)

Three years ago I wrote a paper for the IEA about what I consider to be a moral panic about fixed odds betting terminals (FOBTs). In it, I showed that there has not been a "dramatic proliferation" of betting shops in the UK, whatever Harriot Harman might tell you.

The latest gambling industry statistics were published last week so I thought it was time to see how the bookmaking epidemic had spread since I wrote The Crack Cocaine of Gambling?

Answer: it hasn't.

The latest gambling industry statistics were published last week so I thought it was time to see how the bookmaking epidemic had spread since I wrote The Crack Cocaine of Gambling?

Answer: it hasn't.

Tuesday 7 July 2015

Book Review: Citizen Coke

I wrote a book review for the latest issue of Economics Affairs which is paywalled and was heavily edited for space, so here is the full version. The book is Citizen Coke: The Making of Coca-Cola Capitalism by Bartow Elmore...

Bartow Elmore sees two themes running through the history of the Coca-Cola company. Firstly, the company does not really produce anything; it is a brand, a recipe and a trademark, not a manufacturer. Secondly, it has always depended on government action and political favours to prosper. Elmore argues that these are the traits of ‘Coca-Cola capitalism’, a distinct form of doing business which has since been emulated by other multi-nationals.

On the first point, the author does a convincing job of showing that Coca-Cola has traditionally focused on supplying syrup while leaving bottling, retailing, farming and processing to others. He echoes Naomi Klein’s recurrent complaint about global corporations such as Apple and Gap being mere ‘brands’ which outsource production to other countries. Although Elmore accepts that this has been a demonstrably successful business strategy - limiting risk and leaving the company less vulnerable to changes in government policy - he appears to disapprove, and yet he never fully explains why. The implication is that Coca-Cola somehow lacks authenticity (Elmore calls it ‘hollow’) because it ducks out of the noble task of production. Its preference for outsourcing tough jobs to third parties is portrayed as being almost cowardly, and there is a sense of moral outrage about early Coke retailers who, like McDonalds today, had to mix the syrup with their own water.

It is true that Coca-Cola’s suppliers, including the environmentalists’ bête noire Monsanto, have had their fingers burnt when Coke changed its buying arrangements. Coke’s switch from sugar to high fructose corn syrup (HFCS), for example, was bad news for the sugar industry. But frankly, who cares? Why should the reader empathise with one giant corporation and not another? Even if creative destruction was morally questionable - and it is not - there is no reason why Coca-Cola should pick its own coca or refine its own sugar (as Elmore implies it should). The real question is whether customers get a good deal from the company’s pursuit of efficiency and it seems they do. One of the more extraordinary facts in this book is that the price of a bottle of Coke in the USA remained at five cents from 1886 to 1950.

Elmore’s other main argument—that Coca-Cola’s success owes much to government policy—also contains more than a grain of truth, especially if one uses the author’s broad definition of ‘state aid’ to include access to municipal water supplies and waste disposal. Once again, the company’s success is portrayed as inauthentic and ill-gotten. Throughout the book, Elmore echoes Barack Obama’s notorious refrain ‘You didn’t build that.’ Who built the roads and railways that transport Coke around the US? The government. Who recycles the empty Coke cans? The government. Who provides the water for Coca-Cola’s plants? The government (mostly).

It could be argued that these are indirect benefits of infrastructure projects which would exist with or without a soft drink industry. So long as Coca-Cola pays its taxes and settles its water bills, it has every right to use them. But sometimes the state has acted in ways that directly benefit the company. Elmore makes much of the US army’s extensive distribution of Coke to soldiers in the Second World War and rightly notes that the price of HFCS is artificially low thanks to government subsidies. When expanding its empire abroad, Coca-Cola has often received preferential tax arrangements from governments which welcome new investment. All told, Elmore concludes, the ‘best thing for sleek Citizen Coke was big government’.

It is notable that Elmore rarely blames the government for creating these opportunities, let alone suggests that there is anything inherent about big government that makes such corporatism virtually inevitable. It would be surprising if Coca-Cola, in its long history, had not benefited from rent-seeking, subsidies and good fortune. On the other hand, there have also been instances when Coca-Cola has suffered at the hands of lawmakers—soda taxes and sugar tariffs, for example. Has Coca-Cola benefited from government action more than the average US corporation? Perhaps it has, but Citizen Coke offers little by way of comparison with other businesses.

Throughout the book, the reader is given the impression that the economy is a zero-sum game in which every shrewd business decision is a swindle, every middleman is an exploiter and every win for Coca-Cola is a defeat for everybody else. But whilst Coca-Cola has clearly profited from some government policies, Elmore does not distinguish between those which burden the public and those which benefit the public. It is doubtless true, for example, that the company benefited from the government’s decision to ship countless crates of Coke to American troops during the war, but it did so at the insistence of US army generals who felt that a steady supply of this most American of drinks would act as a boost to both morale and energy. Can we say with confidence that they were wrong? If Lieutenant Colonel John P. Neu, who is quoted in this book, believed that Coca-Cola was ‘vital to the maintenance of contentment and well being of the military personnel’ we should, perhaps, take his word for it.

Similarly, it is not unusual for local and national governments to offer tax breaks as an incentive for businesses to invest and create jobs. Free marketeers would prefer low taxes for all and an end to rent-seeking, but it is not kindheartedness that compels politicians to provide such inducements, rather it is the anticipation of future employment and taxation. What Elmore describes as state aid often amounts to no more than politicians deciding not to needlessly obstruct commerce. For example, Elmore discusses the negotiations around the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act in 1914. This portentous legislation effectively kickstarted the war on drugs by removing cocaine and opium from general sale. Famously, Coca-Cola had used traces of cocaine in its original recipe and, although these were removed in 1903, the drink still contained de-cocainised coca leaf extract. An early draft of the Harrison Act would have severely restricted imports of coca leaves, whether they contained cocaine or not. Successful lobbying by Coca-Cola led to the legislation being amended to allow trade in de-cocainised leaves to continue. As Elmore puts it, ‘the state had once again sweetened Coke’s supply situation.’

There is little doubt that this exemption owed much to private discussions in smoke-filled rooms. It is unlikely that a smaller company would have been able to bend the ear of lawmakers in this way. Nevertheless, Coca-Cola’s victory came at the expense of no one. The intention of the Harrison Act was to prevent the use of narcotics, not to reduce the appeal of one of the country’s most popular soft drinks. A ban on de-cocainised coca leaves would not have advanced the cause of drug prohibition by one inch. In this instance, at least, Coke’s lobbyists led to better lawmaking.

Unfortunately for readers hoping for an exposé, Coca-Cola’s closet contains very few skeletons and so, in the absence of shocking revelations, Elmore throws everything he can at the company. He repeats long-debunked health claims about caffeine and artificial sweeteners, even implying that Coca-Cola was unnecessarily threatening the health of its customers by using saccharine after it been approved by the Food and Drug Administration. He also gives a sympathetic and credulous hearing to the more extreme views about fructose, sugar ‘addiction’ and obesity, with fanatics such as Michael Jacobson and Kelly Brownell taking centre stage while mainstream scientists are ignored.

Ultimately, Elmore’s critique of ‘Coca-Cola capitalism’ boils down to environmental objections. He spends a great deal of time criticising Coke for using vast quantities of water, sometimes in places where water is relatively scarce. But water is a renewable resource and using it to make thirst-quenching drinks seems perfectly justifiable, particularly since much of the water is undrinkable until Coca-Cola treats it. (Elmore accepts that the company has often come to the aid of governments that are unable to maintain decent water quality, but he portrays these acts of charity as a ‘marketing technique’. At his most generous, he concedes that ‘not all of Coke’s [water-purification] projects were solely self-serving’.)

Readers who are shocked to hear that soft drink companies use a lot of water will find much to be outraged about in Citizen Coke. To these eyes, however, the workings of the Coca-Cola company are neither surprising, nor appalling, nor unique. Elmore’s attacks on ‘agri-business’ are generic criticisms of modern farming that could be levelled at any food or drink company and his complaints about the caffeine industry’s deforestation of South America might be valid, but they would be better directed at coffee drinkers.